ANNOUNCING 4 NEW 4P WORKSHOPS

We are delighted to announce some brand new three-day KTS workshops based on the four “P”s of Experiencing Accents – all happening online:

Phonetics On-Ramp: The Not-So-Intensive

Pronunciation Intensive

Posture Intensive

and

Prosody Intensive

The first offering, Phonetics On-Ramp, is a shame-free, beginner’s guide to learning and teaching phonetics through play, gesture, and community skill-building. Open to anyone who has taken Experiencing Speech, this workshop is designed to fit between Experiencing Speech and the Phonetics Intensive for those who consider themselves novice phonetics users, and at anytime for more advanced users interested in investigated new teaching strategies for phonetics in a KTS-inspired arc of speech and accent training. The workshop will include exercises from the new KTS book, Experiencing Speech: A Skills-Based, Panlingual Approach to Actor Training, available for pre-order now and out next month.

More info and registration here.

As each 4P workshop is announced, Early Bird Registration ($50 off the full tuition) will be available for one week. For the Phonetics On-Ramp, that week starts now!

We often teach consonants* and vowels separately, but I wonder if that can lead to a disconnect for some students who feel that they need to digest two bodies of knowledge in order to understand the “geography” of speech. Really, consonants and vowels share a landscape: the vocal tract. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a single graphic that integrates both types of speech sound and their places of articulation, or one that shows vowels and consonants lying on a single continuum in terms of their airstream (closeness vs. openness of stricture.) Some early phonetic charts did integrate consonants and vowels, and you can see vestiges of that tradition in the current IPA chart where the front vowels line up with the palatal consonants, but I thought I’d try to put it all together into one simplified map that shows everything. It’s not the prettiest thing I’ve ever made, but I think it gets the point across that all these sounds relate to one another in space. Have you seen something better, or do you have your own version of something like this that might be clearer or less Frankenstein-inspired? Feel free to post in the comments!

(You may recognize the top and bottom of this graphic as borrowed from our favorite book. Thanks, Speaking With Skill!)

*I’m talking about pulmonic consonants in this post. Sorry, non-pulmonics! (You know you’re my favorites.)

One phrase stuck out to me in a recent discussion about adapting KTS for short-term goals. It was acknowledged that there are some snake oil salesmen out there selling quick-fix speech lessons. These “one-hour schmucks,” as they were termed, are more than happy to prey on naive clients desperate for an authority figure to “fix” their speech…and fast! KTS teachers, on the other hand, know that there are benefits to a slower, more thoughtful approach.

As someone who had ventured to describe a short-term coaching project, I left the conversation wondering, is there room for efficient, targeted work in the KTS world?

I think there is. There’s a difference between putting the practicality of the work on display in an introductory session and selling a snake-oil cure for a made-up malady. There are some worthwhile things you can achieve very quickly in one session:

- You can help a client feel a connection between shape and sound.

- You can lead a client toward greater kinesthetic sensitivity and a rediscovery of their own speech anatomy.

- You can give the client a sense of agency or choice by presenting multiple articulatory options as possible targets while sensitively discussing the audience implications of those choices.

- You can model openness and discourage prejudice by showing enthusiasm for the wide variety of available choices.

- You can model curiosity and empathy by listening closely to what the client says and acknowledging their point of view, even if the client has a more rudimentary understanding of speech, accent, and sociolinguistics than you.

- You can help a client feel excited at the possibilities for their speech.

Even if there is no follow-up session, I believe achieving these sorts of things, even in a very cursory way, can do good for the client with very little chance of doing harm or contributing in a significant way to linguistic prejudice or shame. Of course, it’s also a good idea to point toward the full scope of the work, to show that, with time and persistence, we can go very deep indeed, and to educate (gently) around issues of prestige and “correctness.” But not all clients want to go speech-teacher deep, and I don’t fault them for being dilettantes. Remembering the root of that word, I want to be cautious about killing a client’s delight by making the work too precious–or (though I love the idea of rigor) too rigorous–too fast.

There are some things that are more difficult to do in an introductory session:

- It’s very difficult to shift a lens or change a person’s worldview, especially with a lecture.

- It’s very difficult to help a person feel less “wrong” in their speech simply by pointing out that there’s no right and wrong.

- It’s very difficult to fully understand a client’s linguistic identity and know the extent of any internalized shame without therapizing the session.

I feel that these are long-term projects (and in the last case, possibly outside my scope of practice.) These long-term projects are also embedded within the more concrete work outlined in the first list above. Explicitly combating prejudice is important work both inside and outside the studio. That said, exploring shapes and sounds also changes our worldview–implicitly and gently from the inside out. And it’s the area where, frankly, I feel most qualified to operate. Is that a cop-out? I hope not entirely–I do facilitate conversations on an inclusive linguistic worldview in longer-format academic contexts with my students. But those sociolinguistic conversations flow out of a trust built from the more concrete aspects of the work. For me, trying to “fix” a student’s linguistic self-concept is just as fraught as trying to “fix” their speech.

When I meet a new client, one who is not sending up red flags about deeply-internalized speech shame but simply wants their smartphone to quit misunderstanding commands (and the client easily acknowledges that poor speech recognition across non-standard accents is a flaw of the device, not the speaker,) I am more than happy to work on the client’s terms, with an eye toward ROI (return on investment, in business-speak.) As an artist who values process over product, I may feel slightly out of sorts typing “ROI,” because that’s not the world I tend to inhabit. But it is a real consideration in the client’s world, and I respect that. I don’t necessarily feel the need to ensure the client’s full buy-in to the principles behind the work, because, as pointed out by another colleague, the principles are for me first and foremost.

That’s my practical side kicking in. I don’t think it makes me a “one-hour schmuck.” At least, I sincerely hope it doesn’t.

I also recognize that not all practitioners will agree with me on that count. We each approach the work in good faith from our own perspective. So the question arises: Do we need to get on the same page about how we conceptualize and apply the principles of the work? I don’t think so. Certainly, we can discuss them, and I think we should. But to nail them down to the point where we ensure agreement amongst ourselves seems a little homogenizing, static, and…well, prescriptive. They’re “principles, perhaps”–and not “rules, definitely”–for that very reason.

Here’s an odd question: What if Speaking With Skill had been written specifically for French speakers (perhaps by Dudley “Chevalier”)? The “vowel calisthenics” figure-8 exercise beginning on page 279 might look something like this…try it out!

Does your mouth feel more French yet?

Sometimes coaching an accent’s posture can be challenging. Students may have different starting places, making relativity an issue. Describing the position of articulators can pose problems for students who can’t yet feel the movement or positioning of their vocal tract. In these cases, I remind myself that (oral/vocal tract) posture can be described not just in terms of a static resting position, but in terms of movement patterns.

One notable way French differs from English is in its inventory of vowel shapes. The French language has a greater ratio of front to back vowels and a greater number of vowels with lip rounding. French also has vowels produced with a low velum (nasal vowels). In the example exercise above, three out of five vowels are front vowels, three have lip rounding, and one is nasal. Two of the vowels ([ɔ̃] and [y]) have two of these features at the same time.

This movement pattern gets my tongue and lips moving independently of one another and mobilizes my soft palate. The frequent repetition of [i] reminds my tongue tip to stay down and positions the blade of my tongue for laminal consonants. The “outrigger” vowels [a] and [u] remind my mouth that not all features are used all the time. It’s a constellation of gestures much more characteristic of French than English. If I can hold on to the “feeling” of the exercise while speaking some text, I end up approximating the posture of a French accent whether I can verbally describe that posture or not.

Using these same vowel sounds, I can build a bridge between the exercise and a stable French posture in connected speech. For no other reason than the fact that three items are easier to remember than five, I might take the most frequent focal sounds from the exercise, ignoring the less frequent [a] and [u], and assign word tokens to them. With my student or client, I initiate an improvised “conversation” using these words, in varying combinations: perhaps French-accented music [ˈmyzik], business [ˈbiznɵs], and bond [bɔ̃d̬]*. From this posture-establishing exchange we can transition into scripted text or real conversation.

Does anyone else do something similar, perhaps with a different accent? Leave your pro tips in the comments!

*(I’m using the voiced diacritic in an unorthodox way here. French voice onset times are shorter than in English. Yes, /d/ is a voiced plosive in both languages, but as an English speaker in French mode, I want to remind myself to switch on the voice earlier than I might normally.)

The points that Jeremy raised in last week’s post are worth weeks of exploration, and I am so grateful for his courage and his insight in bringing his curiosity to this forum. I wanted to stumble my way into this socio-philosophical hall of mirrors with my own questions to bounce around in some attempt at securing my epistemological footing.

In June, I taught an Experiencing Speech with Master Teacher Andrea Caban, and we bumped up against this same issue as we neared the end of the six-day intensive. While the group was quite comfortable with Dudley’s “Principles, Perhaps …” and we were able to jettison (mostly) the unhelpful rhetoric of Standard Speech, we did still have to pause and circle and snipe and pause again when discussing “formality.” I presented the graphs I made at our Teacher Cert (June 2016), with the two-axis, graphed averages of multiple perceptions of one audio sample; I hoped to show that there were multiple ways that we, as humans, could collectively perceive formality.

While the students at that most recent ES understood the point I was making with my ad hoc Excel charts, they took the most issue with (and, yes, I pointed out the quotes!) the “folksy” and “fancy” axis. What we finally agreed upon, after some prodding and elucidation, was that the quotes indicate the context that must always be defined, thoughtfully and carefully, in these discussions. Indeed, it is that context that is often missing from the very concept of “formality.”

Which brings me to my next thought, which is that we haven’t really defined “formality.” What is it? What is this thing to which we are aiming/aspiring/avoiding? In Speaking with Skill, around pages 237 and 238, Dudley brilliantly avoids cornering himself into a definition of this slippery concept. While establishing a firm basis for his separation between prescriptive and descriptive speech, Dudley explains “formal” and “informal” speech based on the contexts in which we might use them — and his hedging around that “might,” with function-based definitions of “formal” and “informal,” leaves us grasping at the clear distinction between the two. The two-axis graph came into being — and our conversation continues — because we haven’t really put this debate to bed yet. In fact, we’re still wrestling with the philosophical challenges posed by prescriptive models while also trying to reach audiences who have been reared on the expectations of prescriptive pedagogies.

So that leaves me with my initial question: what is “formality,” really? What is “formal” speech, how does it arise, and how do we define “formal” speech in different contexts? I think Dudley was writing (quite consciously) to the assumption that “formal” speech is meant to suit the needs of older theatrical standards, attached to all of the historical biases inherent in that paradigm. But can there be “formal” speech amongst familiars? Does formality tie into an awareness of audience (while still allowing integrated and authentic communication), such that formal speech is consciously activated to achieve intended communicative goals while informal speech is that which is unconsciously or habitually enacted (though, mushily, perhaps subconscious activation of formality could still occur)? Can someone use speech, informally, that sounds formal to others (and perhaps not to themselves)? The diagonal line on Jeremy’s final graph is reminiscent of Dudley’s orientation toward a “formal”/”informal” scale that reflects upon the context he was raised in and eventually fought against. I’m inclined to get rid of any such vestige of the Old Ways, but I also crave the simplicity of a horizontal axis that supersedes the “folksy”/”fancy” scale. I’m imagining some sort of social scaling — and buying myself a world of eventual hurt — whereby the listener gauges the speaker’s location on a “Perceived Target Audience” scale, ranging from “idiolectal” to “widest possible audience” (based on the speaker’s perceptions, and not on some “objective” standard).

It’s so complicated that it’s worth sussing out, and we may not get to have our clean, horizontal axis until we’ve banged our heads against the wall a few more decades. But I think we can get there, and I definitely think it’s worth the struggle.

A few weeks ago, fellow KTS-er Julie Foh and I presented together in Singapore at the VASTA conference. Our topic was “Linguistic Detail in Singlish” and I was thinking a lot about, well, linguistic detail…but also the idea of formality. And I stumbled into a can of worms.

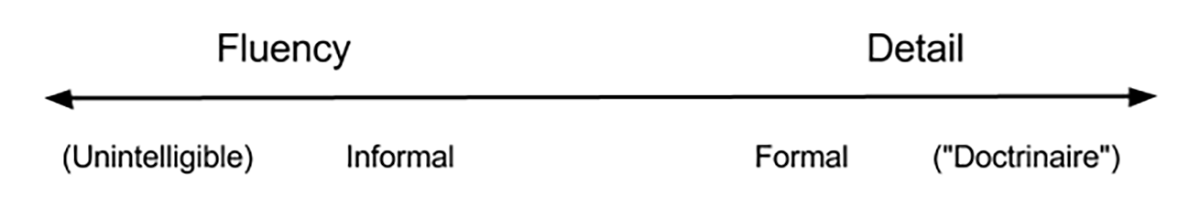

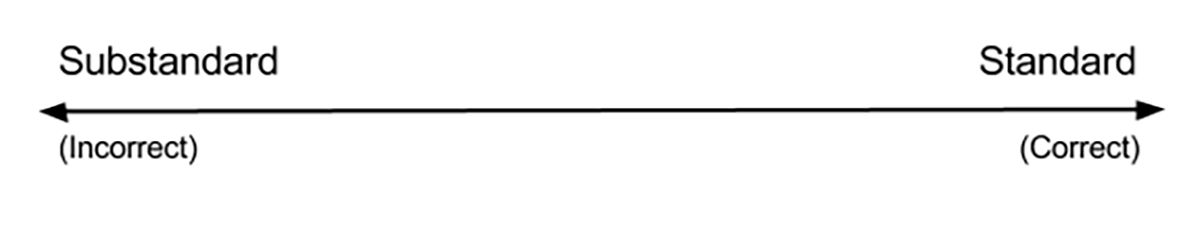

One of Dudley’s innovations in Speaking With Skill is to avoid prescribing a standard accent for formal speech, focusing instead on a continuum of detail and efficiency. The reasoning behind this innovation is an awareness of the classism and racism inherent in the sort of traditional binary formal speech model represented here:

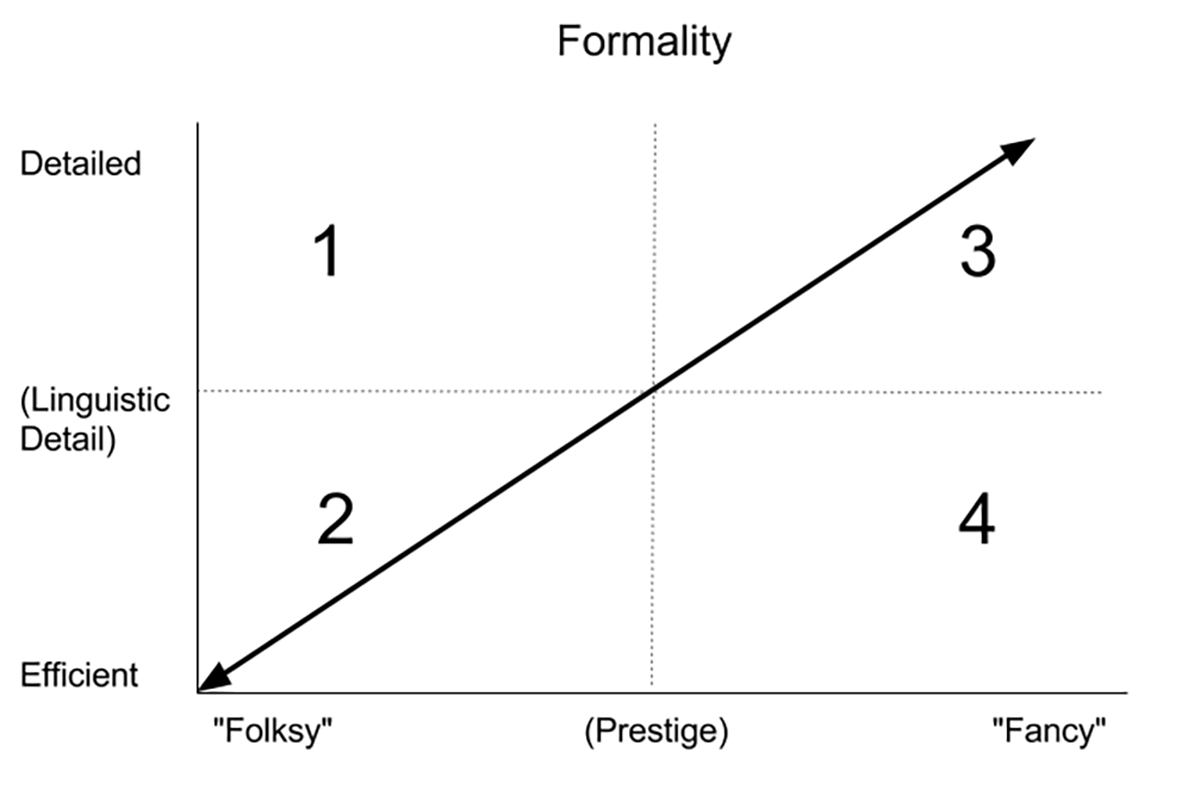

This model confuses prestige for intelligibility. For comparison, here’s a graphic representation of Dudley’s model from SWS:

This model puts detail and formality on the same continuum and ignores prestige entirely. In SWS, Dudley acknowledges social prestige as one measure of formality before intentionally excising it from his model, writing, “There are many good reasons for learning the skills of formal American English speech. But social prestige is not one of them.”

This shift in perspective is perfectly in line with the “Principles, Perhaps” Dudley sets out in the Preface to his book. His model serves the needs of the modern actor. It tries to place a firewall between social biases and the work. And, perhaps most interestingly, it adds a layer of complexity that “nourishes art.” Dudley’s model is unquestionably a principled step forward in speech training.

But…is the concept of formality implicitly coded for prestige? Dudley hinted at this in his brief nod to the “real world” problem of social bias. He suggests that the problem has diminished somewhat over time, and dismisses considerations of social prestige from the physical speech explorations in SWS. In doing so, he moves the conversation around speech training in a positive direction. Indeed, making speech-based social stigma a thing of the past is a goal I think many of us share in promoting this work.

But social bias persists, and Dudley acknowledged this. We may have abandoned a pervasive, prescriptive standard at the top of the formality scale, but there continue to be speech choices that convey more or less social prestige. We still find opinion pieces about policing young women’s voices and online “tournaments” for the “ugliest” accent. Despite the idealism that points us toward a model of formality that dismisses social prestige as irrelevant, we do not live in a prestige-deaf society any more than we live in a color-blind one. And just as the idealistic concept of colorblindness has been criticized by social scientists who argue that a colorblind ideal actually props up institutionalized racism, and that moving toward color-consciousness is an important step towards anti-racism, perhaps we can begin to incorporate an explicit awareness of prestige in our model of formal speech without abandoning our egalitarian ideals. Should we be prestige-conscious in our quest to celebrate all the sounds of human speech?

We began to explore these ideas in the KTS Certification Program last summer. Pardon the math (there’s a picture coming up!)– but what if the one-dimensional continuum we’ve been using all along were to become the hypotenuse of a two-dimensional coordinate plane? Phil Thompson originated the idea, and it looks something like this (although the labels change from time to time):

In this model, Quadrants 2 & 3 describe the convergence of the traditional prestige model and Dudley’s detail continuum. We have speech that ranges from fancy and detailed to folksy and efficient. Many real-life speakers will cluster along this line. But we can now account for a much broader range of actual human variety– for instance, speech that is both “posh” in accent and very fluent and relaxed (Quadrant 4,) or “down-to-earth” in accent and highly articulate and complex (Quadrant 1.)

In a final transformation, we can erase the diagonal line and leave the field open for exploration. We can speak about detail and prestige without conflating the two. In this model, the concept of formality becomes more complex and human. And rather than avoiding the realities of social prestige in human societies, we can continue to identify and guard against our biases, avoid stereotype, champion diversity, and tell real stories through a direct consciousness of the ways prestige, detail, and formality interact.

Several questions present themselves, and so I’ll end this post, as I often do, by offering my curiosity. Does this chart still describe “formality,” or does this new two-dimensional space have a better name? Are there other dimensions yet to be explored– a z-axis perhaps? Would Dudley approve? What’s next?

I recently attended a two-day webinar devoted to transgender voice and communication training for voice clinicians. It was a fantastic experience, and I would recommend the training without hesitation. Even in a super-inclusive and culturally-sensitive environment, people are bound to put a foot in a mouth occasionally– we’re only human, and our implicit biases often slip under the radar. The workshop leaders acknowledged this at the outset, and called these slips “teaching moments”– opportunities to clarify our thinking and our language.

At one point, someone said that they didn’t teach “uptalk” to trans women, because it wasn’t “assertive.” My cultural context radar went off, and I decided to invite a teaching moment. The workshop leaders were wonderfully receptive to my email, shared it with the group, and facilitated a rich conversation about standards and biases. It felt so good to be part of a group that welcomed this kind of inclusive dialogue, and I was reminded of my experience with KTS.

This was the email I sent [edited slightly for clarity]:

A little food for thought on “uptalk”…

This is a cultural phenomenon originally related to the prosody of a legitimate accent (as all accents are legitimate) and shouldn’t be minimized as “these kids these days.” It doesn’t automatically signal uncertainty or lack of assertiveness– that’s making a generalization about a group of speakers who exhibit a behavior that’s not normative, based on the listener’s own cultural lens. It’s simply an inflectional variety. Treating it like a personality disorder simply because it’s not “standard” ignores a great variety of English inflection patterns outside the prestige patterns of so-called General American and RP. Valley girls are not the only (or first) group of people to use rising terminal inflections. This relates DIRECTLY to the topic of this seminar. This is an instance of “difference, not disorder.” [ed.: It’s an important distinction for therapists to make, and this phrase is one that’s taught in SLP courses.]

I grant that it can be useful to teach an acrolect, or the “voice of power,” to a client. Certain patterns convey certain messages. But they don’t convey the same message to all people– they’re not universals. The message you convey depends as much on your audience as on your intention. I grant that it may not be useful to teach uptalk to a client in most instances. But I would like to see us all take care not to stigmatize non-standard varieties, especially in our professional settings– in the words of speech teacher Dudley Knight, we should try to “place a firewall” between our own inevitable aesthetic biases and the work we’re doing.

I think it’s part of our job to call out our own and others’ assumptions about “others”…including girls from the valley. Any prescriptive standard model we teach needs to be explicitly identified in terms of who it represents, what power systems it reinforces, and tempered with a healthy dose of cultural context. We ought to be very aware if we’re hiding our individual preference for a hegemonic standard behind the label of “assertive” speech– whatever thing we may imagine that to be. If we’re choosing not to teach uptalk because it’s “less assertive,” let’s make sure we say to whom it comes across that way. That may mean de-centering our own identities a bit, and it’s work that we must do.

It’s easy to feel self-congratulatory about starting a good conversation, but I’ve been the one with the foot in my mouth just as often. What’s your favorite “teaching moment” story?

From Jeremy:

In the last two posts, we (the editors) introduced ourselves and let you eavesdrop on one of our conversations. But enough about us! We’d like to hear from you. The big question I’m wrestling with today is:

In a college accents course, how many accents should be covered, and which ones?

Here’s a little more background…

At the end of last term, I asked the students enrolled in my accents class what about the course was useful and what needed work. Everyone agreed that oral posture was a revelation and super-useful. Many were frustrated by the phonetics– as was I! (In my first semester at a new school, my upper-division students still have limited phonetic training. For now, we just had to do the best we could in terms of specificity.)

I also inherited a course description, and knowing very little about my student population going into the course and having limited time to do a bunch of brand-new accent breakdowns, I used the “generic” accents that had been included in previous semesters: RP, Cockney, American Southern (whatever monolithic thing that could possibly be), Ireland (again…), Brooklyn (pickin up on a pattern here?…), and German. We did end with individual accent research projects based on type or heritage, so that was a win in terms of customization.

So here’s my curiosity: is covering a lot of ground— painting with broad strokes as it were, gaining familiarity with the repetition of a process and practicing bravery through diving in over and over– worth the losses we incurred in terms of rigor and specificity? Considering the students are not prepared to tackle detailed phonetic work at this point, I was mainly concerned with giving them lots of opportunity to try accents out without fear of failure. I’m happy with that decision, but going forward, I’ll have to find ways to add rigor without losing delight. Fewer accents, probably, with a selection of accents that is generated in-class by the students themselves based on their needs and interests. They loved the idea of picking the accents themselves. At the same time, they want more “play” time– the kind of improv and skills-challenging stuff Phil calls “Reindeer Games”– how to fit it all in?

So…Teachers: how do you wrestle with this issue?

Actors: what do you consider indispensable from your accent training?

Coaches: what do you wish your clients had picked up in school, if they went through an actor training program?

We’d love to dive even deeper into this topic with you, so give us your feedback and help us shape the conversation to come! We can’t wait to hear your thoughts!

Hello, Readers!

If you haven’t had a chance to read our last post yet, make sure you do that before diving into this post. As we begin to experiment with the format and mission of the KTS Blog, we’ve been asking each other questions, about the work and our relationship with it. Our post last time prompted some responses that got us all sorts of curious, and we couldn’t just let those responses stand uninterrogated. So we share with you this week our responses — and our responses to our responses — to some of our initial lines of inquiry.

JEREMY: I’m thinking about your oboe performance story: If technical mastery is one ingredient of the performance stew, can we consider the mental/emotional/spiritual ingredients all aspects of “play?” As I was reading your story and thinking about the playfulness of KTS– Omnish, “Reindeer Games,” etc– I thought to myself, “If we don’t play, we get played”…by our anxiety! How does your experience with learning to include your whole self in your preparation help you with clients? Do you have a sensitivity, intuition, or “super power” with those who might ignore or resist playfulness?

TYLER: With retrospect, I’m able to look at that event now and have pity on my young self, seeing how I had not been trained in adapting to the flow of the present. I didn’t have any helpful beliefs in practice and in performance that would equip me for stress. What I’ve learned since, through advanced training, is that all parts of experience are integrated, connected, and inseparable. Technical mastery, however it’s developed, blends seamlessly into presence, which blends seamlessly into awareness, which blends seamlessly into my inner life in the moment of performance. Preparation occurs in a different context than performance, but in both contexts, I’m looking for that wholeness, that integration of experience that brings all of me onboard and into the circumstances in front of me. This unity of experience could be grouped under “play,” though I suspect it extends deeper and wider than that word suggests.

I look for the same subjective qualities in my work — as actor, as teacher, as coach — as I do in my students’. Specifically: am I coming from a place of ownership, even in imperfection or incompleteness? am I curious rather than following a map? am I breathing? am I allowing this experience to change me, even as I create it? At this point, I think I’ve developed a sensitivity for when these overlapping forces are not in play, though I also think most of us possess that same sensitivity (to differing degrees).

When work in myself is blocked or resisted, I feel a sort of alienation or disembodiment from it; when I see that blockage or resistance in others, I feel a sympathetic response that tells me something’s not quite right, that the experience I’m receiving is removed, put on, or tentative. As an accent coach and teacher, my work with these resistances often comes back to finding ownership through curiosity, using whatever tools I can, in the room, with my student. I wish I had learned to play the oboe with a like-minded curiosity, as opposed to aiming to execute music as a series of mechanical gestures. I remain grateful, though, for the many ways in which my Carmina Burana experience shaped all that followed — and for the lessons that it’s still teaching me!

Last week, you mentioned your “monkey” and your “robot.” Tell us more about those terms, especially for those of us who may not know what that means. How do those qualities manifest in your teaching? How do they manifest in your students’ work? Are there any specific ways you’ve found a balance, in either your work or your students’, that you find particularly effective?

JEREMY: Well, the “monkey/robot” trope is something I picked up in the Knight-Thompson certification– a handy, evocative way of talking about different ways of knowing things. My “monkey” is the part of me that enjoys rolling around on the floor and making funny noises. It’s the part that cracks jokes in class. It’s the part that asks fewer “serious” questions and enjoys impulsive, playful doing. My “robot” is the part that researches, analyses, asks questions and looks for right answers. Both of these characters can be described in so many ways– I’m always thinking, “Yes, that’s true…and also…” when I try to pin them down. But you probably get the gist.

As a Very Serious Child, the robot feels safe as a persona. It’s also limiting for me (as a teacher, as a person) when I stay there for too long. The monkey feels riskier and takes some practice for me, but it can be really, really satisfying.

Striking a balance between the monkey and the robot is a big part of my teaching journey. Individual students are more monkey-like or robot-like. Whole groups of students can also lean one way or another. My job is to recognize their differences and try to respond to their needs. That’s a tricky game, because none of us is pure monkey or pure robot. Sometimes the robots need a robot interface to follow along, but sometimes they need a monkey to take the wheel in order to grow. The monkeys get sad if I run a class with no monkey business, but sometimes they need a robot to help them work strategically and with rigor.

This term, I’ve started letting my students see “behind the curtain” with this issue, just as Phil, Andrea, and Erik did in the certification. The students can just tell from the beginning that I have a sophisticated robot, but I have been paying special attention to the monkey at the beginning of the term, and stating explicitly that humor is important in the work. I cop to the fact that voice and speech work in my class can sometimes get a little heavy or precious, and I invite my students to help me combat that by bringing their senses of humor to class with them. It’s a work in progress, but it does feel– so far– like this semester is flowing better than previous ones.

So, Readers, what do you think? Where do you see traces of the Great Monkey v. Robot Debate of 2016 in your work or teaching? What sorts of strategies do you use to facilitate the different learning approaches of your students? Are these issues in any way related to your experience of performance, speech, or accents?

Let us know in the comments below!